| Introduction | Unit Directory | Contact and Links |

Manchester

Through the stories of many renal units there was some tension between the established local “voluntary” hospital -often with a medical school attached -and the later municipal hospital, albeit historically both arose from former infirmaries or workhouse. This often arose because a renal unit would be opened in the old voluntary hospital, but for reasons of space had to be moved on to the municipal hospital. This certainly occurred in Leeds, Newcastle and Kings College, London. In Manchester renal units were developed at roughly the same time, in Manchester Royal Infirmary (below) and Crumpsall Hospital (page 8), leading to a degree of rivalry.

The Origin and Development of Renal Failure Services in Manchester and the North Western Health Region.

RWG Johnson MS;FRCS; FRCS Ed

On returning from the USA in 1974 I was actively recruited to join the University of Manchester Department of Surgery. Iain Gillespie the Professor of Surgery was anxious that renal transplantation should continue to develop and that a research base should be established. In my estimation Manchester had always had a superb reputation in Renal Medicine and I relished the idea of helping to develop renal transplantation as a multi disciplinary service with the renal physicians.

On arrival the Royal Infirmary provided something of a culture shock; the buildings could, at best, be described as Victorian shabby chic. Suffice to say the corridors were overly well ventilated and required the strategic positioning of buckets when it rained, a not unusual event in Manchester.

The only remaining nephrologist was Dr Netar Mallick with whom I was to form a close co-operative working relationship and a lifelong friendship. There were other redeeming features: tissue typing had been set up, independently from the Regional Blood Transfusion Service, in the excellent Clinical Genetics Department under Dr Rodney Harris. The MRI also had first class diagnostic facilities including Nuclear Medicine led by Tito Testa, Interventional Radiology including excellent Ultra Sound and a CT scanner led by Professor Ian Isherwood. There were also superb renal histopathology,chemical pathology and haematology and microbiology services with interactive clinically orientated laboratory consultants in all those disciplines keen to collaborate.

Manchester’s reputation in renal medicine was based on the clinical acumen and extensive scientific writings of Professor Sir Robert (later Lord) Platt, Professor Sir Douglas Black, and Dr Geoffrey Berlyne who was Reader in Medicine. Professors Platt and Black had been principally interested in the etiology and classification of renal diseases and their management. They had shown little interest in the development of techniques for treating renal failure by dialysis and both had left before I arrived. Only Dr Berlyne had shown an interest in dialysis and he had also departed.. for New York

In 1960 Lord Platt had received the gift of a Kolff twin coil artificial Kidney Machine which he promptly re gifted to the Urologists. Thomas Moore the senior consultant urologist was keen to have dialysis available for patients in acute renal failure. He expected his registrars to master the necessary techniques and to provide a dialysis service on a very occasional basis.

The first dialysis in the North West Region was carried out in Manchester at the MRI in1960 by Philip Clark who was then a senior registrar in urology. The first patient was a lady, in acute renal failure following an operation to treat bilateral renal artery stenosis. Unfortunately she eventually died because her kidneys did not recover.

Philip Clark had been encouraged to take an interest in dialysis by

Mr D S Poole-Wilson a brilliant and far sighted Consultant urologist. Poole-Wilson had purchased a Kolff machine and with and Philip Clark and later David Morrison continued to develop acute dialysis at Crumpsall (North Manchester General Hospital). working at. Prior to performing the first dialysis at the MRI, Philip Clark had visited Dr Frank Parsons in Leeds to learn about dialysis and on one occasion to meet and hear the renowned Dutch nephrologist Dr Fred Boen lecture on the subject of “Peritoneal Dialysis” - a therapeutic alternative not used in England at that time.

At the Manchester Royal infirmary Acute dialysis continued in a rather desultory way over the next 4 years. Dr Geoffrey Berlyne had taken on the main responsibility for supervising dialysis but the work was done by the registrars and the nurses.

Berlyne was keen to start a chronic dialysis programme which did eventually get under way in 1965. (See Linda Whitworth’s description of her experience as a junior staff nurse).

The whole process for both acute and chronic dialysis was conducted in side wards off the main medical corridor. The rooms were small, hot and cluttered; the facilities were totally inadequate for aseptic procedures. Things were made even worse by the presence of of a large water bath used for heat exchange.

In 1966 an hepatitis epidemic broke out spreading largely as a result of poor hygiene and defective aseptic practices. Six people were effected including Geoffrey Berlyne. There was one death a hospital porter. As a consequence the already unpopular chronic dialysis program was abandoned.

Acute dialysis continued at North Manchester General Hospital and had become well established. Chronic hospital based dialysis had started at Withington Hospital in South Manchester under Dr Tony Ralston later aided and abetted by Dr Peter Ackrill.

In 1968 the discontinuation of dialysis treatment at the MRI created a major problem because the Renal Transplant programme was just starting and needed acute dialysis support. A compromise was eventually negotiated by Dr Netar Mallick whereby new clean, spacious accommodation was commandeered on the ground floor of one wing of the Private Hospital. A very strict barrier nursing and hepatitis screening programme was instituted under the supervision of the Regional Virology Service.

Two rooms were set aside for transplantation and the rest of the space was to be utilized for home dialysis training. Home training was slow and very expensive to set up. It took three months to train each patient and to alter their homes and install their equipment. It clearly was not going to serve many of the population.

The first renal transplant operation in Manchester took place in 1968. Mr W McNiell Orr who had trained in Boston and Mr Eric Charlton Edwards a newly appointed urologist, carried out this first cadaver transplant together. Their collaboration was short lived; the urologists pulled out of transplantation for unspecified reasons leaving Willy Orr and Dr Netar Mallick the nephrologist to continue the work on their own. 52 renal transplants and two liver transplants had been performed in the six years between 1968 and 1974 when I arrived in Manchester.

Willy Orr had developed angina and been obliged to reduce his activities. As a consequence he had moved sideways into an NHS General Surgical post, ostensibly dropping his commitment to the transplantation service. In fact he continued to share the work with me for another six years. An excellent surgeon, an astute doctor and a wise councillor he was a joy to work with.

I had trained in Newcastle and in San Francisco prior to my appointment in Manchester. I’d been introduced to transplantation by Professor John Swinney and continued under Professor Folkert Belzer in Dr Dunphy’s department in San Francisco. Oscar Salvatierra and I were assistant professors working full time in transplantation under Dr Belzer. In San Francisco we were doing large numbers of cadaveric and live donor renal transplants, in excess of 100 adults and children per year, with no barrier nursing and no hepatitis screening. Fred Belzer was was a vascular surgeon by training and Oscar was a urologist with a special interest in paediatric urology, as a result I was privileged to receive essential additional experience in vascular surgery and urology especially paediatric urology.

Research was an important part of the units activity which made it a very stimulating place to work.

Clinically, as in Newcastle, a multidisciplinary approach was adopted and both units sought to provide a complete service to as wide a population base as possible both in the Northern Health Region and in Northern California.

This was a new philosophy for the North West Region. The renal failure services in the NW were at a very early stage of development. The total provision for all renal failure services for the whole region, populated by more than 4.5 million people, was for less than 100 new patients per year.

Furthermore there were only six Intensive Care units (ITU’s) in the whole Region all closely associated with the four Neurosurgical Centers and the three Cardiac Surgical Units. Three of the four Neurosurgical Units and all of the ITU’s were happy to co- operate with the proposed organ donation programme; in particular Dr David Morrison at Crumpsall Hospital (North Manchester General Hospital) was already providing an acute dialysis service in his ITU and had been doing so since 1962. He also had one long term chronic dialysis patient using the machine three times a week. This turned out to be a key event in the development of renal failure services in the North West.

In my first year (1974-75) we managed 35 transplants among them a lady who’d been on dialysis at Crumpsall for a number of years. As soon as she was successfully transplanted David was persuaded to take on another patient for chronic dialysis in her stead.

This new patient was a 23 year old man, a bus conductor married with three children. I had been asked to assess him for transplantation and I was shocked to discover that he’d been turned down for dialysis on grounds of lack of moral fibre. I approached David and and persuaded him to take the young man on in place of the lady who’d recently vacated the chronic dialysis place on David’s unit. Fortunately a cadaver kidney became available for the young man quite quickly and he was successfully transplanted.

I returned from holiday a month later to find him lying moribund in one of the two transplant beds. He was uraemic with a grossly swollen leg and there were no plans to dialyse him.

David Morrison had already filled his place at Crumpsall and he, David was very angry at the lack of dialysis support being offered at the MRI. He had called the Chairman of the Regional Health Authority to complain. The Chairman in turn had brought the Regional Medical Officer back from holiday in France to sort it out. All hell had broken loose!

In the mean time I had found that the swollen leg was due to extravasation of urine around the transplanted kidney. A hastily inserted transplant nephrostomy resolved the acute problem. It transpired that the transplant ureter had sloughed and the problem was finally solved by attaching his native ureter to his transplant renal pelvis.

In due course an official enquiry was held at the RHA and I found myself in the dock. It was considered an act close to criminal negligence to have used the acute dialysis facility at Crumpsall to support a chronic patient. I had visions of dismissal in disgrace. Fortunately David Morrison was made of stronger stuff and had brought the, by now fully recovered, patient along as a witness. David stood up to the RMO and the board, pointing out in no uncertain terms that he had been providing both acute and chronic dialysis therapy for longer than anyone at the MRI. The boot was very soon on the other foot.

As a result of the enquiry A study was instigated to be led by Dr Netar Mallick, into the need for renal failure services and the strategic and financial consequences. The enquiry was conducted on a comparative basis with other Regions. It soon became apparent that the provision of renal failure services in the NW Region was lagging a long way behind most other comparable Regions and a plan was put in place to correct it.

This included setting up a second chronic dialysis programme at Crumpsall and in due course new adult dialysis services in Salford under Dr Stephen Waldek and Preston under Dr Robert Coward with children’s dialysis services at Booth Hall under Dr Robert Postlethwaite.

It may be said that these enquiries and the consequential planning should have been implemented years before and indeed that had happened in Newcastle, Birmingham and in the London Regions but they were the exception and not only for renal services but also for many other new services that were emerging in the late 60’s. Forward planning has always been a bit of an anathema in the UK especially when the probable outcome was likely to be expensive. Nonetheless from then on we had total co-operation from the Regional Health Authority for “planned” development of the service. It was to be some time however before we were able to adjust the age limit for entry to the programme to above the age of 40 years and below the age of ten years.

Constraints on the chronic haemodialysis programme were such that we were obliged to set up an early transplant without dialysis initiative.

This involved:

• Early entrance to the transplant list,

• Active development of a living donor programme

• Cadaver transplantation on the basis of least number of mismatches i.e. not sharing locally collected kidneys unless they were of a rare blood group or a perfect match existed else where.

Those constraints continued until 1982. The big change was brought about with the appointment of Dr Ram Gokal who set up Chronic Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis (CAPD) which as Dr Boen had demonstrated 22 years before gave excellent results at low capital cost.

Suddenly we were able to take on much larger numbers of patients; it was no longer necessary to transplant patients urgently pre dialysis with little prospect of life saving dialysis if the transplant failed.

We very soon took over the whole of the ground floor of the Private Hospital providing 15 rooms for transplantation. Home Dialysis Training moved into a very large former sitting room with two single rooms for CAPD training. Accordingly patients were offered a wider range of dialysis treatments and as a result the future transplant recipients were much fitter than previously.

During those years we were able to increase the number of transplants consistently to more than 150 per year. We were fortunate to have long term continuity in our nursing staff under Sister Linda Whitworth and we were also able to recruit excellent new surgical colleagues Neal Parrott, Robert Pearson and Hanny Riad. We were supported throughout by Barry Chapman our Chief transplant Co-ordinator and a series of experienced surgeons and nephrologists in training many of whom have gone on to set up or join transplant units throughout the UK and indeed in many parts of the world. They are too numerous to list comprehensively but I must acknowledge: among the surgeons in training: Andrew Raftery, Geoffrey Cohen, Geoffrey Koffman, Martin Wise, Patrick Scott, John Connolly, Malcolm Holbrook, Robert Pearson, the late Ali Bakran, Velokaren J Joss, Mark Welch, John Abraham, Hanny Riad, Titus Augustine, Tunde Campbell, Argiris Azderakis, Karoy Kalmar Nagy, Maria Marcos and Afsin Tavakoli.

Among the Physicians in training: Robert Coward, Laurie Solomon, Francis Ballardie, Charles Newstead, Colin Short, Alistair Hutchinson, Donal O’Donoghue, Philip Kalrah,

Three other major advances occurred coincidentally:

1. We had been involved in the preliminary studies of the new immunosuppressive agent Cyclosporin (CYA) and with the arrival of CYA and the use of low steroid regimes both patient and graft survival improved dramatically.

2. We appointed Dr Phillip Dyer and Dr Sue Martin who completely reorganised our tissue typing and set up Dr matching which allowed us to minimise sensitization by avoiding Dr mismatches.

3. Children’s transplantation which had been carried out in the adult unit was transferred to Royal Manchester Children's Hospital at the insistence of Dr Robert Postlethwaite. This idea seemed incredible at first but after lengthy discussion and much compromise it was agreed. At the Children’s Hospital, surprise surprise, we had access to specialist anesthetists, specialist children’s intensive care and expert paediatric nephrological management form Robert Postlethwaite, Nick Webb and Malcolm Lewis. In short a truly integrated interactive team and we were able to start transplanting much younger children down to the first year of life. Furthermore we were able to extend our service to include children from the Mersey Region, running combined Clinics with the Liverpool paediatric nephrologists.

Independent National Comparative Audits became a regular feature of transplant meetings in the late 1980’s. Initially there was a wide spread of results for patient and graft survival across the transplant centers in the UK. This “Centre Variation” caused great anxiety and led eventually to the reorganisation and relocation of a number of UK transplant centers. As a result organ collection and distribution were rationalised, transplant numbers per center increased and the gap between the best and worst center results across the country rapidly narrowed.

Patient fatality after renal transplantation had become a thing of the past; failing grafts could be removed early and patients transferred back to the safety of dialysis to await a second, third or fourth graft. Indeed most centers were achieving 95% one year graft survival.

Late graft loss remains a problem; there are numerous causes of which chronic rejection is but one; others include recurrent disease and nephron exhaustion from tubular injury during in vitro preservation.

In a relatively short time renal transplantation has moved from the experimental to an established and reliable therapy with a better profile in terms of quality adjusted life years than most other surgical treatments.

oooOOOooo

Dialysis at Crumpsall Hospital – Later North Manchester General Hospital

David Morrison M.B., Ch.B.

Formerly Director of Intensive Care, Coronary Care, and Dialysis Units

North Manchester General Hospital.

In 1962 I was 29 and looking towards a career in Surgery. I had qualified in 1958 and had been conscripted into the army in 1959. I had managed to get myself seconded to the Ghana army, and had done two years in Ghana and Congo. On return to England I had taken a couple of general surgical jobs to be going on with, when an S.H.O. job in Urology with Mr. D.S. Poole-Wilson came up. This didn’t seem to offer any wild excitement to a young surgeon wishing to give his all, but it changed my life!

Poole had vision. He believed that any G.U. Surgeon worth his salt would want to do transplants one day, and would need to know about dialysis in order to keep patients alive long enough to transplant them. At that time Philip Clark was Tommy Moore’s urological senior registrar at the Royal Infirmary. (q.v.), and had performed the first dialyses there, after a visit to Leeds to learn from Frank Parsons. He was appointed as consultant urological surgeon at Leeds in the early sixties. Poole Wilson sought his help and they conspired together to purchase a Kolff Twin-coil (Travenol) machine, and this had been installed in one of the old staff rooms in the Theatre. Philip had had this room fitted with a Belfast sink, and had installed a fifties style kitchen unit to hold the disposables. Philipconducted the first dialyses in Crumpsall there.

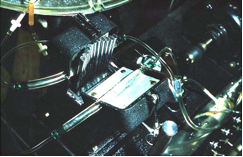

The Kolff machine was American, using American voltages. To get around this, a very large transformer had been bolted to the chassis under the blood pump. This was fine when the tank was full of fluid, but tipped the machine over when it emptied, so several large iron bars were bolted to the other end of the chassis to balance it up. The blood pump was a peristaltic pump with metal fingers pressing on two special chambers in the arterial line. The dialysing fluid in the main tank was heated by a bar heater. A circulating pump pumped fluid into the coil holder, and a similar pump was used for emptying the tank through a hose hitched over the edge of the sink. A metal tube was provided for bubbling a gas mixture of oxygen mixed with 5% CO2 through the fluid in the tank to act as a buffering system.

Dialysing fluid was made up on the spot from dry chemicals and tap water. Philip had found a large plastic bucket of about four gallon capacity. The chemicals were weighed out by the Pharmacy into glass bottles, kept in the kitchen unit. Unfortunately, the salt inevitably set like concrete, and had to be dug out with a screwdriver! The chemicals were mixed by hand (literally) with warm water in the bucket before pouring the solution into the tank. The volume was then made up to a mark on the side of the tank using warm tap water from a hose. The pH was checked using standard laboratory pH papers, and a couple of dollops of lactic acid from a bottle on the shelf used to bring it down to 7.4. Judging the size of dollop came with practice.

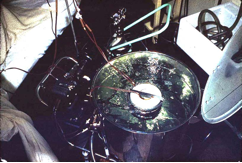

Not long after I had taken the job, we performed the first dialysis (on 22nd. September 1962). The patient was a rather elderly lady who eventually turned out to have obstructive uropathy from Ca bladder. To obtain blood flow into the machine, Phillip cut down on a saphenous vein in her groin. The cannulas which he used were about 10” long and made from tapered plastic tubing. The tubing was about 5mm in diameter over half its length, tapering down to 2-3 mm. The technique was to introduce this through a nick in the saphenous vein and push it up into the iliac, stretching the vessel. When a suitable diameter had been reached, and the vein about to split, the catheter was withdrawn (using a ligature to control the flow) shortened to about a centimetre beyond the widest point of stretch, reintroduced, and the vessel tied around it. This would usually give a decent flow, but the cannula would often suck on to the vessel wall, and we had to devise ingenious contraptions of elastic bands and tape to keep the cannula under some tension. The return cannula was usually put into a large arm vein. At the end of dialysis the saphenous was ligatured and the wound sutured. This obviously limited the number of dialyses which could be performed, but the aim of the manoeuvre was to treat cases of recoverable short-term acute renal failure. This may have been the aim, but turned out not to be the practice!

|

|

|

The first ever dialysis at Crumpsall in 1962. Above Mr.Poole-Wilson watches Philip Clark, watched in turn by Dan Curtin (Medical Registrar) In shadow on the left is Mike Hall (Senior Urolog. Reg.)

Above R. the coil and bubbling gas.

Below R. The peristaltic pump opened to show tubing

I was far too junior to be considered part of the team; I was, however, allowed to clean the machine after use. Two teams had been nominated to be on call for emergency dialysis, led respectively by the Senior Surgical and Senior Medical Registrars. By the time the third patient presented, all of these personnel including Phillip, himself, had left the hospital for pastures new. I was the only one left who knew how to use the machine. I did every dialysis from then on until 1969.

I don’t really know what was happening in the Teaching Hospital (the M.R.I.) at that time. There was little contact between our unit and the physicians or surgeons in Urology there. We, of course, were regarded as barbarians beyond the pale by these divas of medical practice. Professor Platt was the doyen of the renal medicine department, but had no interest in dialysis, as far as I was aware. Douglas Black was Reader, but hardly the practical dialysing type. I gather that Geoffrey Berlyne, the other Reader, was the one who began dialysing chronic renal failure patients in 1965, but where he got his experience from in the first place, I’m not sure. I’d always assumed that there must have been some acute dialysis going on at the Infirmary prior to this, but my wife, who was a student at about the time, can’t recall anything being done when she was there. The medical personnel of the department were not renowned for their interpersonal relationships. I had a great respect for Geoffrey Berlyne (who was the nearest thing to a genius that I met in my younger days) and once asked him to teach me how to do a renal biopsy. After telling me that I was a barbarian from the sticks who shouldn’t be allowed within several miles of a renal patient, he kindly showed me how to do one, and we became, if not friends, at least respectful acquaintances. Within about a year of Geoffrey starting the M.R.I. unit there was a disasterous outbreak of hepatitis which became famous.

The other Manchester unit involved in dialysis was at Withington, started, I think, by Tony Ralston, but here again I don’t know exactly when it started or whether it was involved in treating acute failure before it was set up as a chronic unit. Under Peter Ackrill, who I think trained under Berlyne (he was one of the staff who contracted viral hepatitis in the MRI unit) it evolved to become one of the official Regional Units.

Meanwhile, I carried on dialysis at Crumpsall. My first innovation was to have the chemicals packed by the Pharmacy into sealed plastic bags, which eliminated the need for a screwdriver. I then managed to purchase a new roller blood pump working at British voltage, and to get rid of the transformer and iron bars. My G.U. job brought me into constant contact with the X-ray department at the hospital, and I discovered the Seldinger technique of cannulation, which they were using for aortography. I discovered from the Journal of the American Society for Artificial Internal Organs that Stanley Shaldon was using Teflon catheters and glass heparin perfusion units for repeated dialyses, and adopted these as quickly as I could find a source from which to purchase them. I then read about Scribner shunts, but one could only buy the raw material in the form of Teflon tubing at the time, so I had to teach myself how to draw out tips and to dilate the tubing with a heated mandrel to make leak proof joints for the horseshoe. The shunts were a revelation. Eventually it became possible to buy preformed Silastic shunts. With my surgical background, shunt insertion was a simple practical manoeuvre.

Having done the S.H.O. job for Poole, I broke off to do a Casualty Officer job for a year, still thinking of doing Fellowship, and then rejoined Poole’s unit as Registrar. He told me firmly that he would only employ me if I promised to do Fellowship, and assured me that he would help me “to the very hilt” Having asked him for a couple of days off to do the exam a few months later, and then found that I couldn’t go because he was away lecturing in the States, and the same thing occurring at the next occasion of the exam, I gave up the idea! In any case, I was becoming much more interested in post-surgical management, the treatment of biochemical disorders, intravenous nutrition, and what might be described as the “medicine of surgery” rather than operative surgery. Being known as a “gadget man” thanks to dialysis, I also became involved in setting up a cardiac arrest service for the hospital, and in the long-term ventilation of patients. At this point, I decided that my real interest lay in Intensive Care, and I went to meet Sherwood-Jones at Whiston Hospital, about thirty miles away. He told me to give up what I was doing, and do anaesthesia instead, with a view to finding an I.C.U. job. I did a job as S.H.O. in anaesthetics at Crumpsall, still looking after dialysis in my spare time. We were still only dealing with cases of acute renal failure. In 1968, I was allowed to spend a couple of weeks study leave at Whiston

.

Working for Sherwood-Jones was inspirational and I learned a great deal. In return, I shunted a young lady who had chronic renal failure, and had been rejected by the Regional Unit at Liverpool. She had been assessed after a single peritoneal dialysis, and rejected on psychological grounds because she had been a bit bolshie about her diet. I persuaded Sherwood to take her on. Sherwood had been doing acute dialysis on a Kolff machine in his I.C.U., but, like the rest of us, was not supposed to take on chronic patients. I shunted her and dialysed her for him. I got the best dialysis figures that he had ever seen, simply by dint of wrapping the coil in crepe bandage so that it fitted snugly in the bucket. The lady came out of coma, and turned out to be a wonderful patient with whom he almost fell in love. Within a few weeks she was rowing on the river and going to London to look at the Queen. Unfortunately for me, Sherwood was terrified of knives, and insisted that I drive out to put shunts in for him.

On return to Crumpsall I was allowed to build a two-bedded pilot Intensive Care Unit of my own, and made Medical Assistant to run it, with the promise of a new eight bedded unit in 1970. During the time in the pilot unit, I treated several patients with acute renal failure, and was now my own master when it came to patient selection, so results improved. Towards the end of 1969 I had a patient who developed renal failure following a very severe obstetric haemorrhage. She did not recover for some months, and we had to continue dialysis as a chronic patient. She had been referred to the M.R.I unit, but they were unable to take her into their chronic programme. We managed her for a year, but she then felt that she no longer needed dialysis, and she remained well without it for almost another year. She then had to go back onto the machine. Bob Johnson had now taken over transplantation at the M.R.I., and he transplanted her successfully. In return, I was asked if I would take on an M.R.I. patient for whom there was no space.

Bob had the problem of an insufficiently large pool of transplant patients on dialysis for him to be able to use all the kidneys becoming available from Manchester donors. These had to be sent elsewhere. Having now been made a consultant, I suggested to him that we should build an extension to my I.C.U. which could cope with up to a dozen patients on chronic haemodialysis, and would act as a holding unit for potential transplants. Having an attached renal unit meant that my nursing staff would be circulated through it for training, would take it on as part of their I.C.U. duties (rather than having to recruit specifically for dialysis against the fear of the hepatitis threat) and would be covered for sickness and holidays by the I.C.U. and C.C.U. staff, all of whom would be trained. After violent opposition, we won our case and built a pre-fab unit. We could never run to full capacity with a night shift because of transport problems, but we made a significant contribution. When I retired in 1989 a nephrologist was appointed and a new I.C.U. built together with a proper dialysis unit. Acute cases were still managed in the I.C.U.

I should mention, perhaps, that we stuck to using Kolff machines for many years mainly because the staff were used to them, and also because there was no laying up to do and the viral risks lower.. The original coils had been modified to reduce the priming volume by using hard plastic between the cellophane so that it patterned the tubing and created turbulent flow rather than laminar. The machine itself was modified to enable continuous dialysate flow from a large tank. Fluid concentrate became available rather than using dry chemicals, bicarbonate based fluid made gas bubbling and dollops of acid redundant. Eventually Travenol could no longer supply coils, and we changed to all-singing all-dancing computerised machines using cartridges or capillary tube dialysers. I installed a reverse osmosis water purifying system pumped round the unit when the water board started to use alum to decolorise peaty water (Manchester water had previously been ideal) and installed large reserve tanks when it threatened a strike. Speaking of computers, I programmed my own records system, and could send MRI patients to their review clinics with chemistry results displayed in graphics on a single sheet of paper, which didn’t matter if it happened to get lost.