Patients with renal failure were managed conservatively before dialysis was available. They were put onto a low protein, low salt, low potassium and high energy diet, as experimentation showed that this reduced the rate of deterioration of blood tests and, in particular, avoided dangerously high potassium values and fluid overload. Malnutrition was a consideration in patients on some of these very restrictive dietary regimens. The diet was relaxed over the years as dialysis became available.

Conservative treatment before dialysis was available

Acute renal failure

In the 1940s the concept of using diet to preserve life until the kidneys recovered from an insult was developed. Recoverable acute renal failure was called Acute Urinary Suppression; now we would call it

Acute Tubular Necrosis

Diets like those shown below were the alternative to dialysis in the early days – and in the absence of dialysis, they must have saved lives. Control of fluid and salt intake were probably at least as important as the protein restriction. Dietary management remained important in patients treated by dialysis, but the diet could be relaxed a little.

Two diets for acute renal failure They contained almost zero protein, strictly limited fluid, and no salt.

Borst, 1948 (Amsterdam) Daily intake in acute renal failure:

| Two diets for acute renal failure They contained almost zero protein, strictly limited fluid, and no salt. | |

| Borst, 1948 (Amsterdam) Daily intake in acute renal failure:

Given as a gruel; provided 1750 calories. |

Bull, Joekes & Lowe, 1949 (Hammersmith, London)

Dripped in through a nasogasric tube steadily over each 24h. |

Chronic renal failure

Giordano (in 1963) and Giovannetti Maggiore (in 1964) showed that biochemical and symptomatic improvement occurred if the protein intake of patients with severe chronic renal failure was limited to 18 g per day (consisting of essential amino acids or natural proteins of high biological value) (Robson JS, 1969).

Very low protein diets reduce urea production by the body, and this at the very least makes the blood tests look better. It was thought in the 1960s that a low protein diet could delay death and increase life span. They may do that, in the absence of dialysis, but many still died. Protein was restricted to 18 grams per day (protein intake in an unrestricted person is about 60-80 g/day). The 18 grams of protein included essential amino acids, additional essential amino acids or ketoanalogues of essential amino acids were sometimes given to patients. The protein content of the diet was calculated meticulously. The diet was so strict that even Christmas dinner could not be an exception.

| Two examples of components of a Giovannetti low-protein diet (from Mrs E. Sloan) | |

St Cuthbert’s recipe for making gluten-free, salt-free bread

|

Giovannetti Christmas Dinner

Turkey: as usual meat allowance for patient |

| “There was a problem of compliance since the protein did not smell or taste very nice”

“This kind of bread was sold in local Co-op shops in Edinburgh for renal patients and those with gluten-sensitivity.” (Elizabeth Sloan, Renal Dietitian 1974-2001 ) |

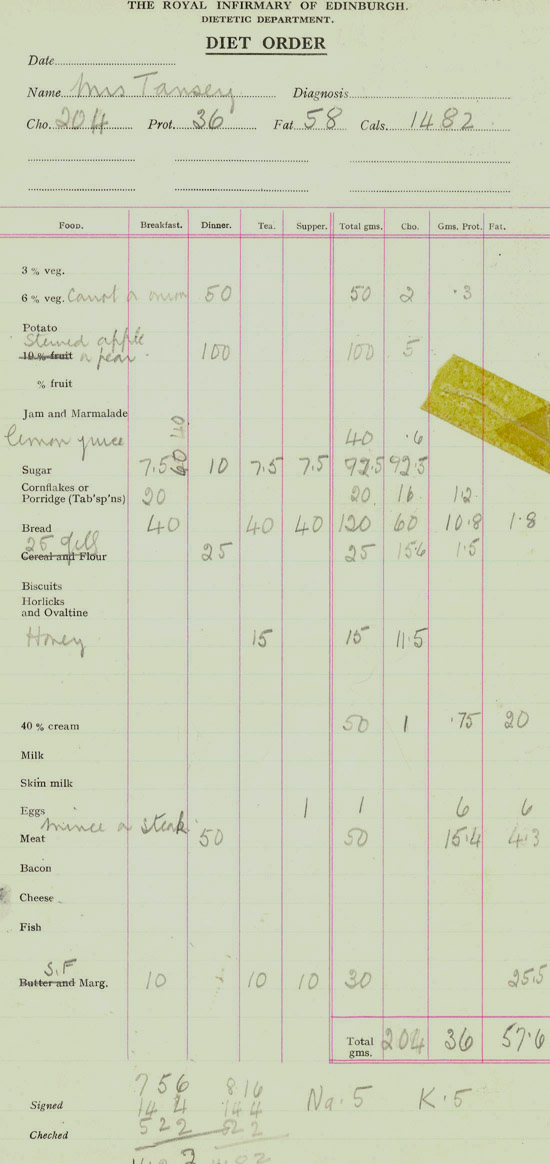

Example of a diet order at RIE dietetic department (1960s):

Diet for patients with chronic renal failure who are on haemodialysis

Standard dietary restrictions in 1960s for patients with CRF on HD were 60 grams of protein per day, potassium restriction, no added salt (salt during cooking was allowed), fluid restriction of 500 ml plus an amount equivalent to the volume of urine output. Patients with poorly controlled hypertension were advised to take a completely salt-free diet although it became obvious that this interfered with the enjoyment of meals so much that it was abandoned. At that time few patients were given anti-hypertensive medication.

By the 1970s and 1980s standard dietary advice for patients with CRF on HD involved a more normal protein intake of 60-80 g/day combined with potassium restriction, no added salt, fluid restriction as before. Increasing attention was paid to phosphate control by dietary manipulation in combination with phosphate binding agents.

Diet for patients on CAPD

When CAPD was introduced in the USA in the 1970s patients had a free diet and fluid intake. They used a very hypertonic glucose solution to draw out excess fluid, but it was later suspected that these damaged the peritoneum, reducing its dialysing properties. Controlled fluid intakes were then introduced along with some degree of salt restriction. Patients were encouraged to increase their protein intake to compensate for the loss of protein during CAPD. Potassium intake was not a problem since it was easier to control on PD – indeed some patients require a high potassium diet to maintain a normal plasma potassium.

Other points

1972 Aluminium toxicity

The aluminium in aluminium hydroxide capsules, used to bind dietary phosphate in patients with renal failure and on dialysis, was found to be absorbed into the body in some people, contributing to “dialysis dementia”, anaemia, and worsening renal bone disease. Calcium carbonate was subsequently used in Edinburgh; other non-aluminium phosphate binders have subsequently been developed.

1980s

Introduction of ACE inhibitors which can cause hyperkalaemia led to more patients (especially those not on dialysis) requiring restriction of oral potassium intake.

The effect of acidosis on nutrition was highlighted – acidosis increases protein catabolism and reduces albumin production.

The debate about using low protein diets in conservative management continued but the philosophy in Edinburgh was that reducing the intake of protein, and thus the acid load, along with the prescription of sodium bicarbonate would control acidosis and minimise risks of malnutrition whilst controlling blood urea levels.

1995 Centralised renal service

Transplant patients, who had previously been treated at the Western General Hospital, came under the care of renal dietitians at the Royal Infimrary of Edinburgh. The dietar considerations for patients after a successful kidney transplant were healthy eating, with an emphasis on lipid intake, normal weight maintenance, and bone preservation by giving calcium and vitamin D supplements.