Alport syndrome is the second most common inherited cause of kidney failure. It most commonly affects young men, but it can affect older people and women. Too much info here? Read an Introduction to Alport Syndrome.

What happens in Alport Syndrome?

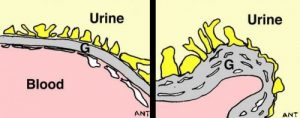

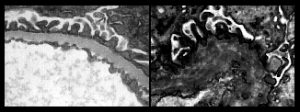

In each of the one million tiny filtering units (glomeruli) in each kidney, blood is filtered across the glomerular basement membrane (GBM). In Alport syndrome, type IV collagen, one of the proteins that makes up the GBM, is absent or abnormal. Although the GBM looks normal in childhood, it deteriorates with time because it lacks the special type IV collagen that should be there (see pictures).

As well as in the kidney, this special basement membrane collagen can also be found in some other parts of the body – most importantly in the inner ear and in parts of the eye.

What trouble does Alport Syndrome cause?

Kidneys: Most people with Alport syndrome develop kidney failure in early adult life – most commonly in their twenties or thirties. Some (particularly women) only get the disease in later life. Before kidney function deteriorates, there may be blood and protein in the urine, and high blood pressure may develop. Women may never get much more than these changes, but some of them go on to get kidney failure over decades.

Deafness: Deafness, at first to high tones, develops at round about the same age as kidney failure in most patients, although this is variable. It gets worse but doesn’t usually make you ‘stone deaf’. With hearing aids most patients remain able to communicate well.

Eyes: Harmless changes may be seen at the back of the eye using special tests. Some patients develop lenticonus, an unusual deformity of the lens of the eye, but usually in middle age. Lenticonus can be treated by lens replacement, just like treating a cataract.

How is it inherited?

Alport syndrome is more common in boys and men because the gene that usually causes it (called COL4A5) is on the X chromosome. Women have two X chromosomes (XX), so they usually have a normal copy as well as an abnormal copy of the gene. Men have only one X chromosome (XY), so if they have a problem with the COL4A5 gene, that is their only copy. Boys who inherit the disease in this way must inherit it from their mother (as the mother contributes the X chromosome and the father the Y).

In other families the gene involved (COL4A3 and COL4A4) is on another chromosome. In this case, men and women are equally affected, but otherwise the disease seems the same. You must usually inherit an abnormal copy of an Alport gene from each of your parents to get this type of Alport’s (autosomal recessive inheritance).

See below for information about kidney disease in carriers, people who carry one abnormal and one normal copy of an Alport gene. Women who are carriers of X-linked Alport’s will pass on the abnormality to half of their sons (likely to get the full disease) and half of their daughters (who will be carriers). A man with X-linked Alport syndrome will pass on the abnormality to all of his daughters (all will be carriers as they all receive his X chromosome) but none of his sons, who receive his Y chromosome.

How rare is it?

In the UK Alport Syndrome accounts for 1% of patients with complete (‘end stage’) kidney failure who are kept alive by dialysis or a kidney transplant; We estimate there may be as many as 2000 affected individuals in the UK, but as we learn about milder genetic abnormalities this may rise.

How is the diagnosis made in the patient and their family?

The diagnosis is usually made after kidney biopsy and from the hearing changes. If someone in the family has been shown to have Alport syndrome, it is not usually necessary for everyone to go through all the tests. Sometimes doing a special test that involves looking at a sample of skin under the microscope can help, but this is not an easy or fool-proof test and it can only be done in some centres. Eye changes can sometimes be helpful.

Other diseases can cause kidney trouble that runs in families, sometimes even with deafness.

Can I have a genetic test?

Genetic tests are improving all the time. They are not simple in Alport syndrome, because the genes involved are very large and it may be difficult or impossible to be certain. However it is now possible to pinpoint the problem by genetic testing in a large proportion of cases. This can be useful when the diagnosis is ‘probable Alport’ rather than definite. It isn’t usually necessary when the diagnosis is already certain, as knowing the result won’t alter treatment.

This is likely to change as we learn more about Alport’s. Possibly in the future genetic tests may be able to predict risk and likely response to treatment. We aren’t there yet.

Can it be cured?

Although it cannot be cured, there is useful treatment.

- Recent information shows that treatment with ACE inhibitors () looks likely to slow down kidney disease.

- Protein in urine can be a warning sign that there is a higher risk of trouble ahead.

- ACE inhibitor treatment (or similar alternatives) should now usually be the norm for patients with a significant protein leak into their urine. Taken over many years this may have a big effect on when dialysis/transplantation are needed. Sometimes it may make the difference between needing it and not needing it (this may be especially true in carriers).

- Complications of kidney failure can be prevented (see chronic renal failure and its progression). If complete kidney failure (end-stage renal failure, ESRF) looks inevitable it is important to prepare for it in good time.

- Exposure to loud noise damages hearing too, so best to avoid that and be careful with earphone volume if you are at risk.

What if kidney failure develops?

People with Alport syndrome are usually otherwise healthy and do very well on dialysis, and even better after a successful kidney transplant.

Very occasionally (in less than 1 in 20 Alport transplants) kidney transplants meet with a unique problem. Because the transplanted kidney has normal type IV collagen, the immune system may see it as ‘foreign’ and attack it. This causes Alport anti-GBM disease, which is very similar to the kidney disease seen in Goodpasture’s disease. Unfortunately it usually destroys the transplant.

What about ‘carriers’?

Carriers are people who have one abnormal copy of an Alport gene, and another normal copy. Mothers of X-linked Alport boys, for example, are always carriers. A kidney biopsy in a carrier is likely to show a thinned GBM, sometimes called Thin Basement Membrane Nephropathy or TBMN.

Women who carry the disease on one of their X chromosomes usually have no or only minor kidney trouble. Tests often show small amounts of blood, and sometimes protein in their urine. However some are unlucky enough to get more severe disease and develop kidney failure. The lifetime risk of getting significant kidney disease for women who carry Alport’s may be as high as 20-30%, but most never get severe trouble, and those who do are usually much older than men who are affected.

Parents of children with recessive Alport Syndrome are also carriers of an Alport mutation. We know less about their risk, but a minority do develop significant kidney disease at some point in their lives. They probably often have Thin Basement Membrane Nephropathy if you biopsy their kidneys.

It isn’t yet known what makes the difference between carriers who don’t get serious kidney disease (that’s most of them), and the unlucky ones who do. That’s one of the important research questions just now.

Where can I get further information?

On this site we have pages on:

- A short introduction to Alport syndrome

- Info on Thin GBM disease

- Further info on the very rare problem after kidney transplantation of Alport anti-GBM disease

| It is really helpful for patients in the UK to join the Alport Patient Group and Registry. This puts you on a list to get further info, and will help to get research going to find better treatments. Contact info@alportuk.org to get on the list for joining, and to get in touch with the UK Patient Support Group. More info about the registries for rare kidney diseases at rarerenal.org. |

There are a number of other valuable resources on the web. Here are a few:

- Alport UK is a very active group, with a helpline and Facebook group.

- Alport Syndrome Foundation – a very active US patient group, also has a discussion forum for patients and a Facebook page

Acknowledgements: The author of this page was Neil Turner. It was first published in October 2000. The date it was last modified is shown in the footer.