This page is about renal angiography. There is another page about angioplasty

What is an angiogram?

An angiogram is a special x-ray examination of blood vessels. Normally, blood vessels do not show up on ordinary x-rays. However, by injecting a special dye, called contrast medium, into an artery through a special fine plastic tube called a catheter, and taking x-rays immediately afterwards, detailed images of arteries and veins can be produced.

Why do I need an angiogram?

A renal angiogram helps to diagnose narrowed blood vessels to the kidney. This can require further treatment, sometimes by angioplasty, or by an operation. Occasionally there are other reasons for having a renal angiogram.

Who has made the decision?

The doctors in charge of your case and the radiologist doing the angiogram will have discussed the situation, and feel that this is the next step. However, you will also have the opportunity for your opinion to be taken into account. If, after discussion with your doctors, you do not want the procedure carried out, then you can decide against it.

Who will be doing the angiogram?

A specially trained doctor called a radiologist. Radiologists have special expertise in using x-ray equipment, and also in interpreting the images produced. They need to look at these images while carrying out the procedure.

Where will the procedure take place?

Generally in the x-ray department, in a special “screening” room, which is adapted for specialised procedures.

How do I prepare for an angiogram?

You need to be an in-patient in the hospital. You will probably be asked not to eat for four hours beforehand, though you may be told that you can drink some water. You may receive a sedative to relieve anxiety. You will be asked to put on a hospital gown.

If you have any allergies, you must let your doctor know. If you have previously reacted to intravenous contrast medium, the dye used for kidney x-rays and CT scanning, then you must also tell your doctor about this.

What actually happens during an angiogram?

You will lie on the x-ray table, generally flat on your back. You need to have a needle put into a vein in your arm, so that the radiologist can give you a sedative or painkillers. Once in place, this will not cause any pain. You will also have a monitoring device attached to your chest and finger, and may be given oxygen through small tubes in your nose.

The radiologist will keep everything as sterile as possible, and will wear a theatre gown and operating gloves. The skin near the point of insertion, probably the groin, will be cleaned with antiseptic, and then most of the rest of your body will be covered with a theatre towel. If the arteries in your groin are blocked it may be necessary to perform the procedure from an artery at your elbow or wrist.

The skin and deeper tissues over the artery will be anaesthetised with local anaesthetic, and then a needle will be inserted into the artery. Once the radiologist is satisfied that this is correctly positioned, a guide wire is placed through the needle, and into the artery. Then the needle is withdrawn allowing the fine, plastic tube (catheter) to be placed over the wire and into the artery.

The radiologist uses the x-ray equipment to make sure that the catheter and the wire are moved into the right position, and then the wire is withdrawn. The special dye (contrast medium) is then injected through the catheter and x-rays are taken.

Once the radiologist is satisfied that the x-rays show all the information required, the catheter will be removed and the radiologist will then press firmly on the skin entry point, for about 10 minutes, to prevent any bleeding.

|

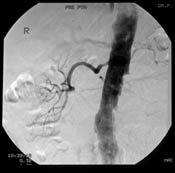

| A renal angiogram showing the renal artery coming from the aorta (the main blood vessel leading down the body). It is narrowed near its junction with the aorta. |

Will it hurt?

When the local anaesthetic is injected, it will sting to start with, but this soon wears off, and the skin and deeper tissues should then feel numb. After this, the procedure should not be painful and you wil not feel the tube moving inside your arteries. There will be a nurse, or another member of clinical staff, standing next to you and looking after you. If the procedure does become uncomfortable for you, then they will be able to arrange for you to have some painkillers as appropriate.

As the dye, or contrast medium, passes around your body, you may get a warm feeling, which some people can find a little unpleasant. However, this soon passes off and should not concern you. You will also feel as though you are passing water as the dye passes through the arteries to your bladder – again this passes off very quickly.

How long will it take?

Every patient’s situation is different, and it is not always easy to predict how complex or how straightforward the procedure will be. Some angiograms do not take very long, perhaps half an hour. Other angiograms may be more complex, and take rather longer, perhaps over an hour. As a guide, expect to be in the x-ray department for about an hour and a half altogether.

What happens afterwards?

You will be taken back to your ward on a trolley. Nurses on the ward will carry out routine observations, such as taking your pulse and blood pressure, to make sure that there are no problems. They will also look at the skin entry point to make sure there is no bleeding from it. You will generally stay in bed for a few hours, until you have recovered. You may be allowed home on the same day, or kept in hospital overnight.

Are there any risk of complications?

Angiography is generally very safe, but there are some risks and possible complications.

Risks to the artery in the groin: Quite often a small bruise (‘haematoma’) forms around the site where the needle has been inserted. If this becomes a large bruise, then there is a risk of it getting infected, and it may require treatment with antibiotics. Very rarely, some damage can be caused to the artery by the catheter which may need to be treated by an operation or another radiological procedure.

Risks to the kidneys: The contrast material used to show up the arteries may temporarily worsen kidney function. This is more likely if you have poor kidney function, are a diabetic, or are taking some particular drugs.

Damage to other arteries: Moving tubes around in narrowed arteries can knock off tiny bits – ‘atheroemboli’ – which fly off and block much smaller arteries in the feet, in the kidney, or elsewhere. This is more likely if the aorta (major blood vessel from the heart) is badly narrowed, and occasionally it causes serious trouble, for instance leading to kidney failure, or a need to amputate toes or even limbs. Very rarely this can be fatal.

It is important to discuss what the risks are in your case with the radiologist and with the other doctors looking after you. The risks are very low for most people, but higher for others.

Finally…

Some of your questions should have been answered by this information, but remember that this is only a starting point for discussion about your treatment with the doctors looking after you. Make sure you are satisfied that you have received enough information about the procedure, before you sign the consent form.

Angiography is considered a very safe procedure, designed to obtain sufficient information about your circulation to allow you and your doctors to make an informed decision about your future treatment. There are some risks and possible complications involved, and although it is difficult to say exactly how often these occur, they are generally minor and do not happen very often. Some people may already have narrowings in all their blood vessels and they are more at risk of developing complications after angiography.

What is the treatment?

If any blood vessel narrowings are found, the possible treatments are discussed in detail with your doctor. The blood vessel narrowing may be suitable for angioplasty or it may be felt that treatment with medication particularly blood pressure tablets may be the best option. You may be asked to partake in a trial comparing different treatments.

| Angiography can usually be done in a very short hospital admission or as an outpatient |

| Usually the risks are low, but in some patients they are higher – you should discuss this |

Acknowledgements: The authors of this page were Ian Gillespie and Neil Turner. It was first published in August 2001 and reviewed by Paddy Gibson in April 2010. The date is was last modified is shown in the footer.