Goodpasture’s disease (also known as Goodpasture Syndrome, anti-glomerular basement membrane disease, anti-GBM disease) is an uncommon condition which can cause rapid destruction of the kidneys and bleeding into the lungs. It was first described by Ernest Goodpasture in 1919, and subsequently his name was given to the disease. However it is now known that several diseases can cause a similar picture. Most physicians reserve the name Goodpasture’s disease (or syndrome) for the disease produced when the immune system attacks a particular molecule that is found in the kidney and the lung, the Goodpasture antigen. Confusingly, some use the term ‘Goodpasture Syndrome’ to refer to any patient with lung hemorrhage and severe nephritis, regardless of which disease caused it.

This is a longer section than most others on our website, because information about the disease is hard to come by and we receive a steady stream of enquiries. A simpler and simpler and shorter version is also available. Note the cautions about all of the information at the foot of the page.

|

|

| Ernest Goodpasture – photo reproduced by kind permission from the Historical Collection, Eskind Biomedical Library, Vanderbilt University | |

The disease

You can have both lung and kidney disease, or kidney disease alone, or (rarely) lung disease alone. Commonly the first lung symptoms develop days, weeks or months before kidney damage becomes evident, although they may occur at any time.

Goodpasture’s disease is rare: about 1 case per million people per year has been estimated in white European populations, and it is rarer than this in most other races. While it has occured in patients as young as 4 and as old as 80, it is most common at ages 18-30 and 50-65. Men and women are almost equally affected.

Kidney disease

The kidney disease primarily involves the glomeruli (filtering units). It is usually only recognised when an explosive acceleration of the disease process occurs, so that kidney function can be lost in days (rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, RPGN; also known as crescentic nephritis). Blood leaks into the urine, the amount of urine passed declines, and fluid and urea and other waste products are retained in the body. This is renal failure. Renal failure only causes symptoms when 80% or more of the total function of the kidney has been lost, and at first symptoms may be very vague: loss of appetite moves on to sickness, and when kidney damaged is advanced, breathlessness, high blood pressure, and swelling caused by fluid retention.

|

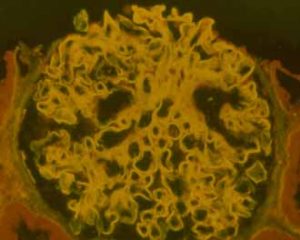

The glomerular basement membrane of this glomerulus is brightly illuminated in yellow by the anti-GBM antibodies that are bound to it. Courtesy of Dr Rick Herriot, Aberdeen |

Lung disease

At its most severe, lung haemorrhage may cause shortage of oxygen so that intensive care and artificial ventilation are needed. However at the other extreme it may only cause dry cough and minor breathlessness. In occasional patients relatively mild symptoms may go back over many years. Coughing up of blood may be a poor guide to how severe the lung disease is, but as with the kidney disease, and often at the same time, deterioration may occur very rapidly. It is often only at this stage that the patient seeks medical attention. Sometimes patients are anaemic because of bleeding episodes into the lungs over many weeks or months. In Goodpasture’s disease lung haemorrhage mostly occurs in cigarette smokers or those with damage caused by infection, fluid accumulation, or exposure to fumes such as paint or gasoline. This is not true of most of the other conditions that can cause lung haemorrhage and RPGN.

|

|

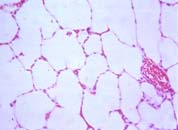

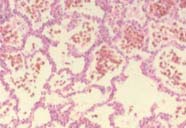

| To the left, normal lung, with lots of air spaces. To the right, the lung of a patient with lung haemorrhage, showing red blood cells in the alveoli. | |

Diagnosis

Because the early symptoms are characteristically vague, and because of the tendency of the disease to undergo very rapid progression, it is common for the true diagnosis to be reached at a relatively late stage. Tests for anti-GBM antibodies in the blood can be very useful. They should always combined with tests for ANCA (Antibodies to Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antigens), as the two types of autoantibody (autoantibodies: antibodies to ‘self’ proteins) can occur together.

Kidney biopsy is almost always necessary. It is often the quickest way to make the diagnosis, and even if the diagnosis looks certain, it may give valuable information about the likely effect of treatment.

Treatment

Effective treatment was developed in the 1970s. This combined several treatments that had been used on their own without much success: most patients died of lung haemorrhage or developed irreversible renal failure. The combined treatment was both more aggressive and more dangerous than had been used before, but it was also dramatically effective. Lung haemorrhage was arrested within days, and further kidney damage could be prevented. The treatment was designed to remove the antibodies which were causing the lung and kidney damage, and prevent the production of new antibody. It was therefore designed to suppress the immune system, and the most important side effects are consequences of this. However it was the first effective treatment for a type of kidney disease that caused renal failure, and therefore a milestone. The major elements of the treatment today are very similar to those used in the early 1970s. These treatments are also described in more detail in the page on Immunosuppressive drugs for renal disease, which is about drugs used to control the body’s immune system. Briefly, the components are:

PREDNISOLONE – a ‘steroid’, a synthetic version of the hormone naturally produced by the adrenal glands in response to stress, but used in high doses. Steroids are immunosuppressive and also damp down inflammation.

CYCLOPHOSPHAMIDE – a powerful drug that works by killing dividing white blood cells to knock back the immune system. It is also used in some cancers.

PLASMA EXCHANGE – a machine is used to remove antibodies from the blood by filtering or spinning to remove the plasma, and replacing it with plasma or purified protein solutions. Immunoadsorption onto protein A columns is another way of removing antibodies that is used in some centres.

Side effects of treatment

The most important is increased risk of serious infection. All three aspects of the treatment contribute to this. All three arms of the treatment also carry additional risks of their own, but it must be remembered that the risks of the disease itself are also substantial.

Duration of treatment

Plasma exchange is typically used for up to two weeks. Three months of cyclophosphamide treatment is usually enough to suppress anti-GBM antibody production, after which it can be stopped and prednisolone tailed off. Relapses after this time are uncommon if a full course of treatment has been given. In some instances they appear to be related to resuming cigarette smoking. Without treatment, anti-GBM antibodies may remain in the blood for a year or more before disappearing. Patients who have ANCA as well as anti-GBM antibodies are generally given treatment for longer than three months.

Deciding not to treat

Because of the risks of treatment, some patients may be best left untreated. These are those who don’t have lung haemorrhage, but who have severe and irreversible kidney damage. This decision has to be taken carefully after the diagnosis is secure, and kept under review.

Outcome

Twenty-five years ago Goodpasture’s disease was usually fatal, but deaths are less common now. Death from lung haemorrhage may occur before the diagnosis has been made or in the first few days of treatment before it has been controlled. Lung haemorrhage may also be reactivated by infection, fluid overload, or lung toxicity (eg caused by cigarette smoking). With treatment, lung disease usually recovers completely. Unfortunately kidneys are less able to repair themselves, and those with severe kidney damage are often left with permanent renal failure and face a life on dialysis treatment or renal transplantation.

Immunosuppressive treatment puts the patient at increased risk of a variety of common and uncommon infections, and acute renal failure remains a severe illness with significant risks, even with the best modern management. This is particularly true if the patient is old or suffering from other diseases.

What causes Goodpasture’s disease?

As with other autoimmune conditions such as diabetes and thyroid disease, the cause of Goodpasture’s disease is not known. A number of things are known that may place people at greater risk of getting Goodpasture’s disease (while remembering that it remains very rare), particularly their tissue type (see below, under Research). There are also some clues to things that might precipitate it. However they are only clues, not answers. Very occasionally people have developed the disease after lithotripsy (delivery of a focused shock wave to the kidney to destroy a kidney stone) or some other kinds of kidney trauma. More commonly, inhaling noxious substances such as cigarette smoke causes lung haemorrhage but most of the people to whom this occurs probably had the disease already.

What else can cause nephritis and lung haemorrhage?

Lung disease and kidney disease occur together quite commonly, and only a minority of patients with trouble in both organs have Goodpasture’s or a related disease. Most commonly, kidney failure leads to fluid accumulation in the lungs. Sometimes this causes bleeding into lungs, usually minor. A few diseases may cause lung haemorrhage with rapidly progressive nephritis, as occurs in Goodpasture’s disease. Most important of these are some which cause inflammation of small blood vessels (VASCULITIS). Those causing lung haemorrhage/nephritis affect the very smallest blood vessels or capillaries. A test for antibodies to certain white blood cells (ANCA) can usually identify these diseases when they are acute enough to cause renal and lung disease, but it is not infallible. The renal biopsy will also usually suggest the type of disease.

Although the initial treatment of vasculitis is usually very similar to that for Goodpasture’s disease, it is worth making the distinction. The results of treatment, and the risks of the disease coming back or affecting other organs, are different. Usually these diseases respond well to treatment. For the kidney, the outlook is better in vasculitis than it is in Goodpasture’s disease.

Renal transplantion

Kidney transplantation can be safely carried out in Goodpasture’s disease after anti-GBM antibodies are no longer detectable. The best advice is to leave an interval of at least 3 to 6 months after the first negative result (this will depend on the sensitivity of the test being used). This may be a problem if no treatment was given at the outset, as the time for safe transplantation may then be 1-2 years away. But these precautions have largely removed the problem of destruction of transplants caused by return of Goodpasture’s disease.

Research

Studies of Goodpasture’s disease have revealed a great deal about how kidneys become damaged, and these findings are relevant to many other kidney diseases besides Goodpasture’s disease itself. The treatment that was designed for Goodpasture’s disease (cyclophosphamide and prednisolone, with or without plasma exchange) is now widely used in the treatment of vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and some other disorders affecting the kidney and other organs. In many of these it is more effective than it is in Goodpasture’s disease, in that kidney failure can be reversed in a high proportion of cases. Studies of the disease continue, as there are certainly further lessons to be learnt from it.

Milestones in Goodpasture research

A few research groups around the world have a major interest in Goodpasture’s disease; ours in Edinburgh is one of these. Britain has a particular history of interest and research into the disease, following on from pioneering work at the Hammersmith Hospital.

Further Info

We haven’t come across many reasonable medical accounts of this type. Let us know if you know of any links that we should insert here.

Acknowledgements: The author of this page was Neil Turner. It was first published in January 2000. The date is was last modified is shown in the footer.