Contents

Why check for proteinuria?

We check proteinuria to help in the diagnosis of kidney disease and to stratify the risk of cardiovascular disease and progressive kidney failure in CKD.

Proteinuria may be due to:

- physiological stress (e.g. orthostatic in a young person)

- haemodynamic stress (e.g. obesity, heart failure)

- glomerular disease (usually high levels of proteinuria)

- tubular disease (low-moderate levels)

- overflow (e.g. from paraproteinaemia)

- lower urinary tract disease

Albuminuria – which usually correlates well with total proteinuria – is a sign of intrinsic renal disease. It is strongly associated with risks of cardiovascular disease and progressive CKD.

When to check for proteinuria

Where proteinuria testing can be transformative:

- suspicion of nephrotic syndrome

- suspicion of intrinsic renal disease (seek help in interpretation and check for haematuria too; even low levels may be significant)

Where proteinuria testing is likely to be helpful:

- new diagnosis of CKD (see rationale below)

- screening in T1DM and T2DM (favour ACEi or ARB if uACR > 3)

- screening in pregnancy

- patients eligible for anti-hypertensives (favour ACEi or ARB if uACR > 30)

Where proteinuria testing is unlikely to be helpful:

- serial monitoring in stable CKD, particularly if proteinuria already high

- to “assess response” to RASi (except perhaps if then considering SGLT2i)

How does proteinuria assessment help in known CKD?

- risk-stratification for CVS disease (although not incorporated into formal risk calculators)

- risk-stratification for CKD progression (and therefore frequency of monitoring, referral – is incorporated into risk calculators, e.g. 4vKFRE)

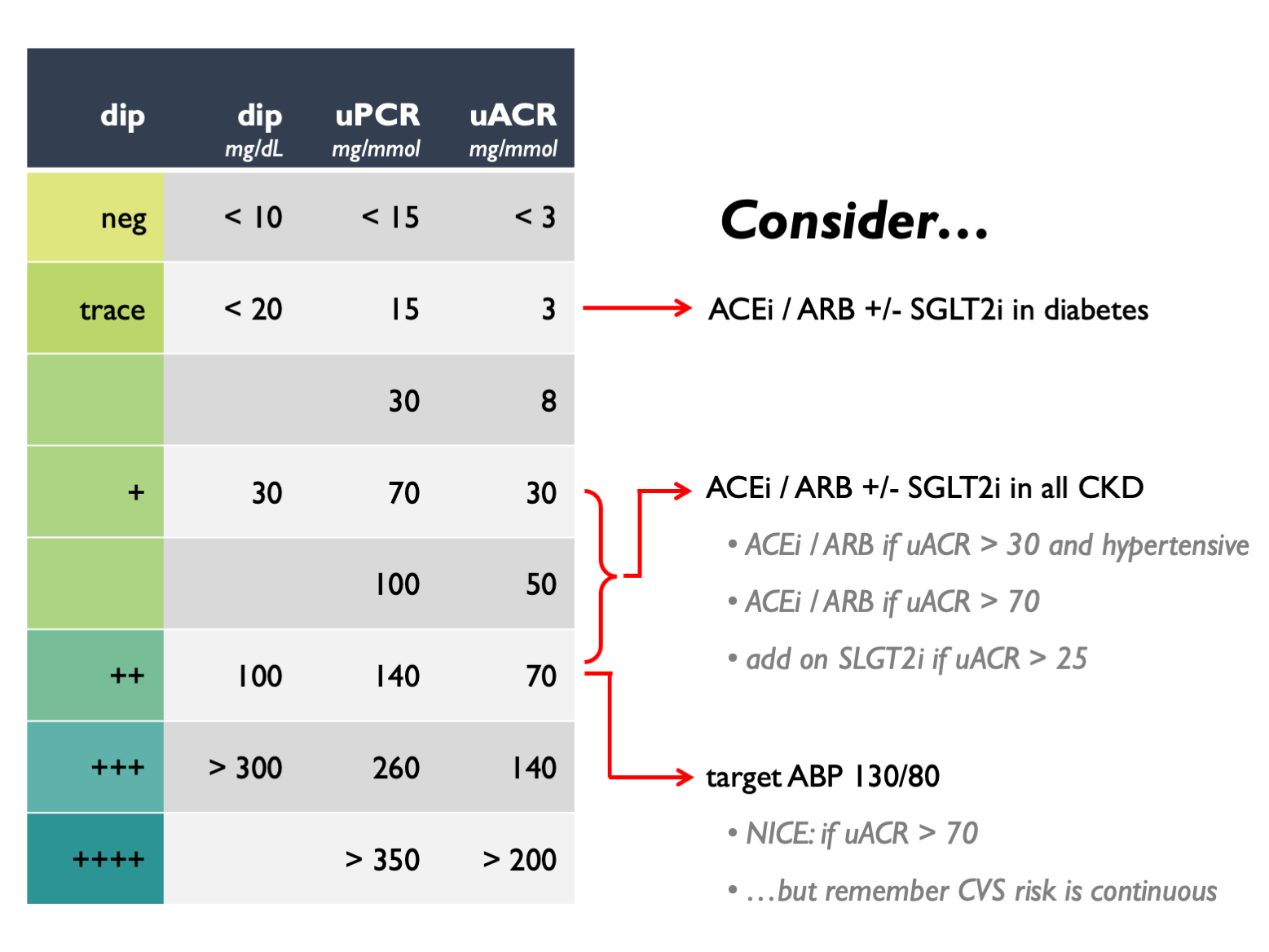

- choice of pharmacotherapy (RASi, SGLT2i, statin – e.g. ACEi or ARB and SGLT2i indicated if uACR > 30 mg/mmol in non-diabetic CKD)

- setting ABP targets

- monitoring response to treatment (can be helpful in selected patients; not usually helpful for most CKD)

Sometimes the additional information provided by proteinuria testing is helpful in nudging a “grey” decision – e.g. may alter threshold for offering statin, setting ABP targets – even if this is not always explicitly protocolised in guidelines. This is often the case in multi-morbid patients with poly-pharmacy.

Full list of scenarios where proteinuria testing is suggested by NICE:

- eGFR < 60

- eGFR > 60 but strong suspicion of CKD

- T1DM, T2DM

- HTN

- previous AKI

- CVS disease

- structural renal disease

- multi-system disease with potential for kidney involvement

- gout

- FHx of kidney disease.

- incidental haematuria or proteinuria

How to check for proteinuria?

Dipstick urinalysis can be used to screen for proteinuria, but the result will be affected by urinary concentration. (Patients with proteinuria but dilute urine may have a false-negative dip result; patients with no proteinuria but a concentrated urine may have a false-positive.)

For more accurate quantification, send a spot urine sample in a universal container. Ideally send an early morning urine, but a random sample will be accurate enough in most patients. Request either an albumin:creatinine ratio (uACR) or protein:creatinine ratio (uPCR). Results are expressed as a ratio to urine creatinine concentration in order to correct for urinary dilution.

Establishing whether a result is a true positive

Persistent proteinuria is abnormal and implies intrinsic renal disease. Check separate samples including an early morning sample to establish that the finding is consistent. NICE recommend: repeat ACR on early-morning sample if initial result is 3 – 70 mg/mmol and consider ACR > 3 mg/mmol as significant.

Transient low-level proteinuria may be detected in:

- acute febrile illness

- urine infection

- exercise-induced proteinuria

- ‘orthostatic proteinuria’ – absent in early morning sample (though this requires monitoring, and may require further investigation if levels of protein are high)

PCR or ACR?

Since KDIGO 2012, guidelines have favoured ACR as this is more sensitive at lower levels of proteinuria, more specific for parenchymal renal disease and more tightly associated with CVS risk, all-cause mortality and CKD progression.

The improved sensitivity is particularly helpful in diabetic patients, in whom RAS-blockade improves outcomes even at very low levels of albuminuria (uACR > 3 mg/mmol). However, the additional benefits are nuanced in non-diabetic CKD and therefore we have tended to use PCR because this is cheap, familiar and intuitively easy to interpret (100 mg/mmol = 1 g per day).

Very occasionally, it can be helpful to check both ACR and PCR (e.g. to support a diagnosis of overflow proteinuria due to a paraprotein). In NHS Lothian, uACR cannot be quantified at very high levels (above 850 mg/mmol), and so uPCR would be better for monitoring serial trends in proteinuria.

The ICE ordersets for CKD diagnosis and monitoring in NHS Lothian will default to uACR (rather than uPCR) from early 2023.

How to interpret results

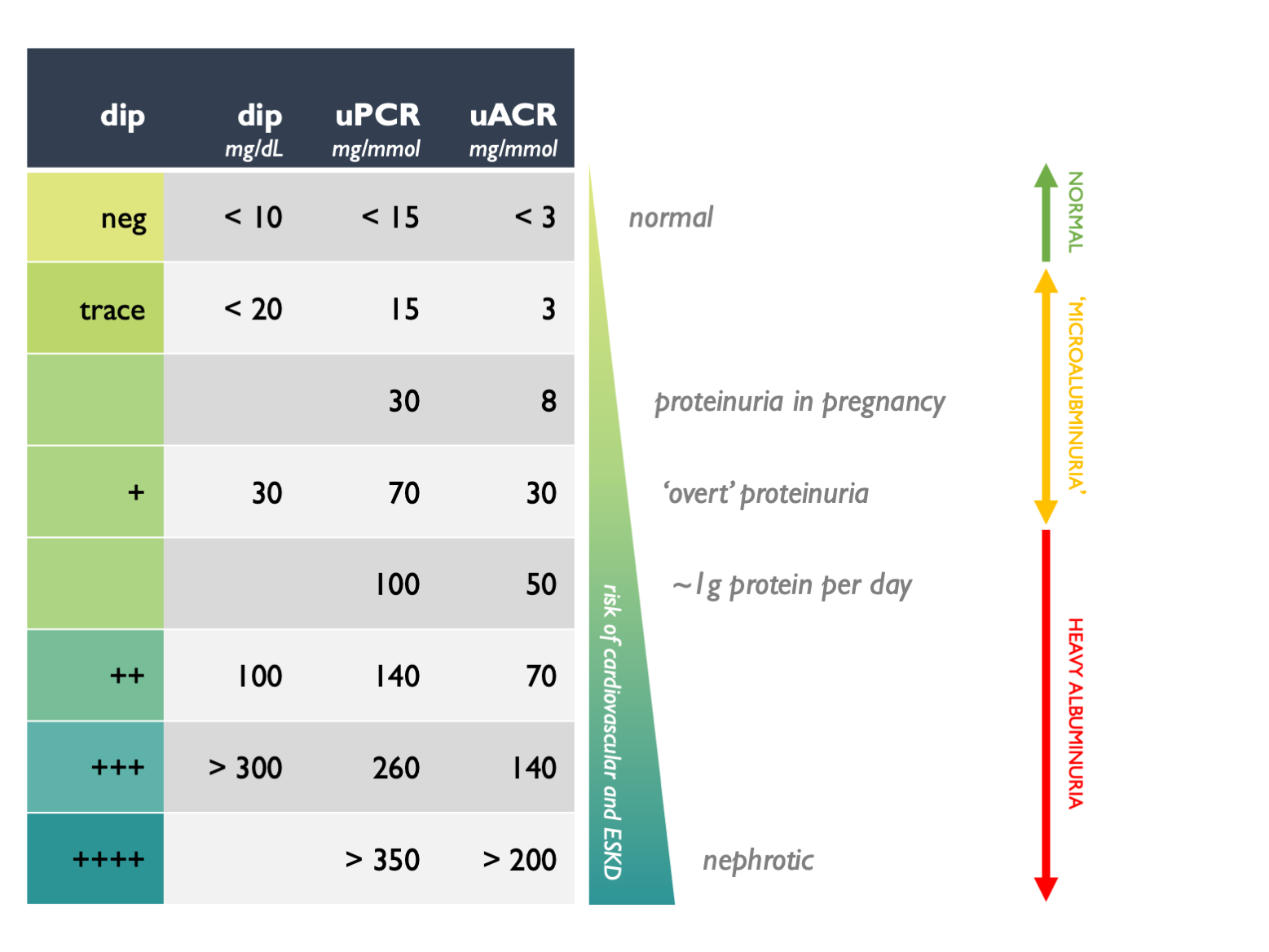

Approximate rules of thumb for interconverting between different measures of proteinuria and for interpreting clinical significance are given in this table:

These are rough guides; the clinical context is important when interpreting proteinuria. Concurrent haematuria and proteinuria suggests intrinsic renal disease, even at low levels of proteinuria.

In the UK, uACR and uPCR results are expressed as mg / mmol. (Take care to note the units as elsewhere they may be different.) Many physicians – particularly those who trained when 24 hr urine collections were used more widely – prefer to think in terms of protein excretion rate (PER), measured in grams / day. As a rough rule of thumb, uPCR 100 = uACR 70 = 1 g protein excretion per day.

Or see calculator and this associated publication for ACR/PCR interconversion, but this is not necessary for routine clinical decision-making.

The following figure suggests how one might respond to proteinuria results in stable CKD – but remember clinical judgement should be exercised and we provide more comprehensive guidance elsewhere on this site:

Abbreviations on this page

- ACEi = ACE inhibitor

- ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker

- CKD = chronic kidney disease

- HTN = hypertension

- KDIGO = Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (international guidelines for kidney disease)

- NICE = National Institue for Health and Care Excellence

- RASi = renin-angiotensin system inhibitors (i.e. ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers)

- SGLT2i = sodium-glucose co-transporter type 2 inhibitor

- uACR (or ACR) = urine albumin:creatinine ratio, measured on a spot urine sample

- uPCR (or PCR) = urine protein:creatinine ratio, measured on a spot urine sample

- 4vKFRE = 4-variable kidney failure risk equation

Acknowledgements

This page was updated in April 2023 by Robert Hunter.